Sign #3 Text:

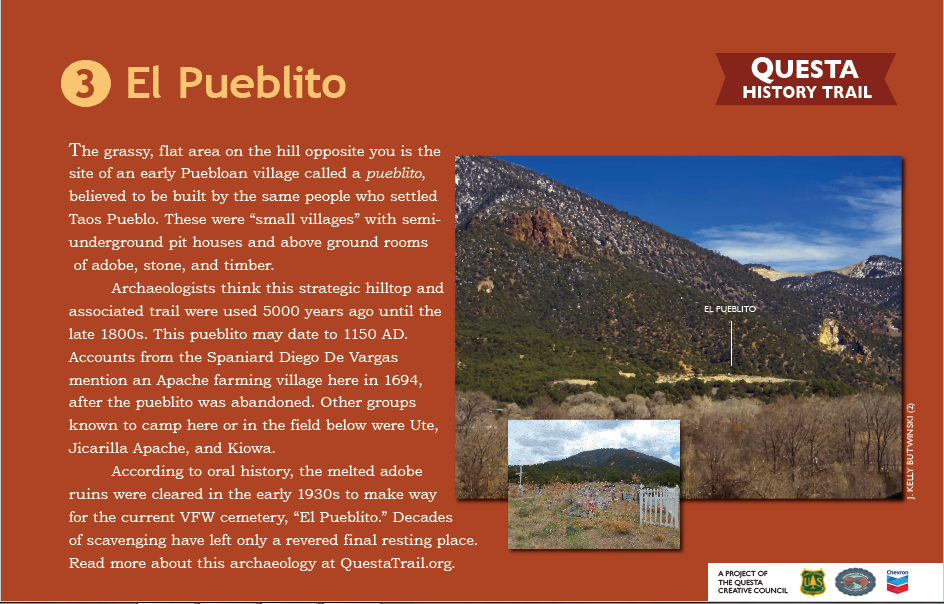

The grassy, flat area on the hill opposite you is the site of an early Puebloan village called a pueblito, believed to be built by the same people who settled Taos Pueblo. These were “small villages” with semi-underground pit houses and above ground rooms of adobe, stone, and timber.

Archaeologists think this strategic hilltop and associated trail were used 5000 years ago until the late 1800s. This pueblito may date to 1150 AD. Accounts from the Spaniard Diego De Vargas mention an Apache farming village here in 1694, after the pueblito was abandoned. Other groups known to camp here or in the field below were Ute, Jicarilla Apache, and Kiowa.

According to oral history, the melted adobe ruins were cleared in the early 1930s to make way for the current VFW cemetery, “El Pueblito.” Decades of scavenging have left only a revered final resting place. Read more about this archaeology at QuestaTrail.org.

The Archaeological History of Questa’s VFW Cemetery

By Carrie Leven, Questa Ranger District Archaeologist, U.S.D.A. Forest Service

Buried beneath Questa’s VFW Cemetery named El Pueblito (“little village” in Spanish) is the site of an ancient little village, also referred to as a Pueblito. Archaeologists think the Pueblito dates from about 1000 years ago, and that people lived there most heavily from 1150 to 1225 AD. Pueblitos sometimes grew into larger, multi-storied Pueblos as more travelers, traders, and families moved in over the generations – as long as there was enough water, timber, firewood, and good farming land to sustain their numbers.

This little village is located on the level hilltop at the mouth of Red River Canyon and overlooks the valley to the west, with the Red River and Cabresto Creek below. This is a long-used camping place along a significant trail known locally as the Kiowa Trail that was used even before the Pueblito was built. People had come to live in the Questa area seasonally in the summer months who depended on hunting game animals and gathering food from the land. With only raw materials to use, they made spear and dart points and other stone tools from the local volcanic rock, like andesitic basalt and obsidian; some artifacts have been dated to 6800 years ago.

As more people arrived over the 1000s of years, they created a trail and established campsites along the way, near their favorite hunting grounds and plant-harvesting spots, returning year after year when the weather permitted. They used metates and manos made of granitic sandstone for grinding and crushing seeds, nuts, and other plant or mineral materials collected in our rich surroundings. They built semi-underground huts called pit houses, using a construction style called jacal, which refers to both the structures made from branches, timbers, mud, and stone. Pit houses were made by digging a deep pit on the side of a hill, then placing upright timbers to support walls and a roof. Soon these early Puebloan people began making and using pottery from local clays, growing crops in the valleys below, and using the bow and arrow for hunting in the pastures and mountains.

Evidence of the Anasazi or Puebloan culture found along the trail are small settlements of pit houses, some of which were abandoned, and others that were incorporated into Pueblitos. Pueblitos like the one at the VFW cemetery had one or two pit houses along with above-ground work areas and surface rooms of jacal. The people living at the Pueblito near Questa used Plains-style Taos Gray and Taos Black-on-white pottery, small corner-notched dart and arrow points, along with metates and manos for processing food and raw materials. The Pueblito was also a trading and travel center, with traders, hunters, and travelers coming from the north and south on this trail that connected with other major trails.

The early camps and more recent settlements at Rio Colorado have several things in common, mainly that it is a beautiful location with both pasturable and farming land nearby, and water from two rivers. The ruins of older villages get knocked down and covered over by those who come after, because the choice location is still the preferred place to settle in and build anew. For decades, people took arrowheads and pottery from the site, removing so many artifacts that now there is little evidence of the former Pueblito for people to see or for researchers to study. Even though they are degraded, leaving nothing on the surface today, this Pueblito and other archaeological sites in the area are protected by Federal Laws with fines for removing artifacts.

Archaeologists think the Pueblito site may be related to the settlement of Taos Pueblo, which also began about the same time. Taos creation stories tell about the Shell people who moved to the Taos Valley and settled near the Colorado River (understood to be referring to the Red River at Questa). The Pueblito site may be ancestral to the Day People kiva at Taos Pueblo. The Shell people were one of the original groups within the Sun or Day kiva, according to anthropologists.

Like widespread abandonments happening at other Pueblitos and Pueblos in New Mexico, the Puebloans left the Pueblito by the mid-13th century. The villagers perhaps outgrew their forested surroundings, suffered deadly droughts as well as harsh weather with unpredictable freezing temperatures; the same issues that affect modern farmers and other people living in Questa today. Perhaps they eventually moved on, joining relatives and clan groups at the growing Pueblo in Taos.

By the 1600s, groups like the Kiowa, Jicarilla Apache, and Ute used the old Pueblito walls for their camps. Spanish accounts from the De Vargas expedition in 1694 mention an Apache farming village overlooking the Rio Colorado. Later accounts from the Spanish Army traveling on the Kiowa Trail in the mid-1700s and early 1800s mention Indian people living in an abandoned village along the Rio Colorado, the low ruins of which were reportedly still standing in 1887. Archaeological studies at the Pueblito concur that the Jicarilla Apache and Ute may have lived at the site through the late 1800s.

The American Foreign Legion (AFL) and Questa VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) have been using El Pueblito as a cemetery since 1933. According to a long-time caretaker, the AFL leveled and cleared the jumbled ruins of the Pueblito and installed a fence to establish the cemetery. Since that time there was repeated grading of the parking area, and backhoe excavations inside the fenced interior. In 1965, the Questa Ranger District issued a Special Use Permit to the VFW for continued use of the cemetery, because it fell within Carson National Forest-administered lands.

In 1999 the VFW received a grant for maintenance and repair on the “El Pueblito” cemetery. They approached the Questa District Ranger about expanding the area, as more Questa residents would need to be buried there, in addition to VFW members/families and other residents. At that time, there were approximately 225 marked graves, with half the cemetery area unused, although there were believed to be unmarked graves in several locations from before 1933.

Because archaeologists believed there may be an older settlement site below the cemetery, they consulted with the NM State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) on an archaeological site testing program to determine if the cemetery could be expanded, and in what direction. In 2000, the Carson National Forest signed a decision that the VFW cemetery could be expanded in a new section to the east, with conditions that burials would stop in the old cemetery after the expansion was completed. Several burials have occurred in the original area after families showed a record of making payments on the plots.

Today, Questeños continue the tradition of burying family and friends and visiting the dearly departed at El Pueblito Cemetery, or just taking a contemplative walk with a beautiful view. While on the hilltop overlooking Questa, we can also perhaps remember and wonder about the people who lived here hundreds of years ago and who are buried along with the remains of the old Pueblito.