Sign #2 Text:

Imagine a walled plaza at your back and below you a distant line of riders on horseback. From 5000 years ago and throughout the initial settlement of Questa, a travel way traversed the land between the Rio Grande Gorge and the Sangre de Cristos.

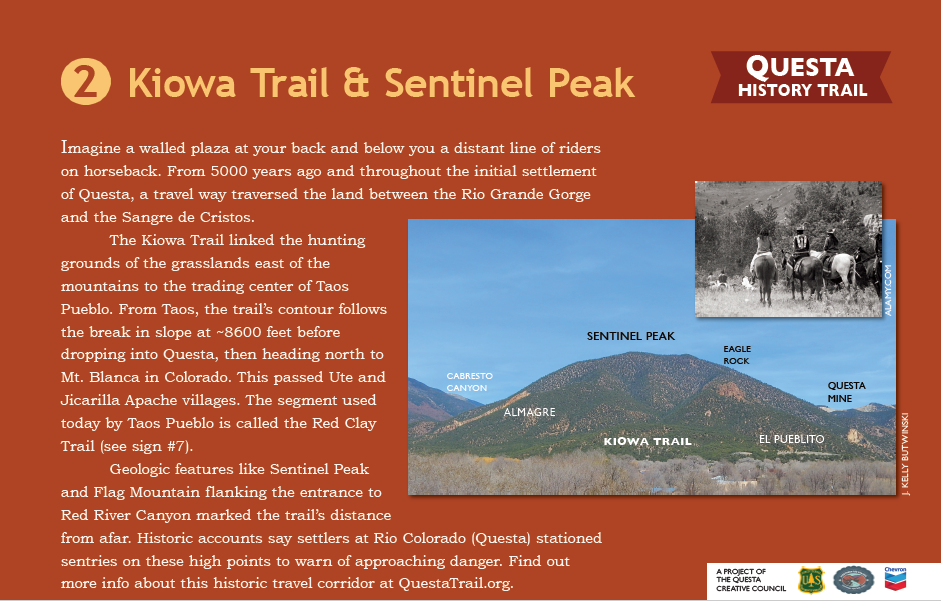

The Kiowa Trail linked the hunting grounds of the grasslands east of the mountains to the trading center of Taos Pueblo. From Taos, the trail’s contour follows the break in slope at ~8600 feet before dropping into Questa, then heading north to Mt. Blanca in Colorado. This passed Ute and Jicarilla Apache villages. The segment used today by Taos Pueblo is called the Red Clay Trail (see sign #7).

Geologic features like Sentinel Peak and Flag Mountain flanking the entrance to Red River Canyon marked the trail’s distance from afar. Historic accounts say settlers at Rio Colorado (Questa) stationed sentries on these high points to warn of approaching danger. Find out more info about this historic travel corridor at QuestaTrail.org.

Kiowa Trail & Sentinel Peak

By Carrie Leven, Questa Ranger District Archaeologist, U.S.D.A. Forest Service

For thousands of years, people traveling to and through today’s Village of Questa used a trail that paralleled the western face of the rugged Sangre de Cristo Mountains. This route on the east side of the deep Rio Grande Gorge was known locally as the Kiowa Trail or El Camino de los Kiowas, but was also called the Taos Mountain Trail, Trapper’s Trail, Tewa Trail, and Sangre de Cristo Trail. It travelled from the buffalo hunting pastures of the Kiowa-Rita Blanca National Grasslands east of the Rocky Mountains to the trading center at Taos Pueblo. The close relationship between the Kiowa people and Taos people is shown in their shared “Kiowa-Tanoan” language.

Prominent geologic features like Sentinel Peak and Flag Mountain that flank the entrance to Red River Canyon marked the distance on the trail from the north and south. These mountains and their knolls gave a commanding view of the Rio Grande Valley below. Historic accounts say people living at Rio Colorado (an earlier name for Questa) stationed sentries on these high points to raise signals and warn of approaching danger on the trail. Villagers took advantage of the protected location on the mesa, at the same time the height of the jagged mountains and depth of the valleys between Taos and Questa created additional challenges for access to villages.

Trails begin to form along travel-ways because the path of least resistance is usually mutual. Animals on their seasonal grazing rounds created game trails that are still in use today. Man-made trails followed animal trails, because hunters were following game, or shepherds following their herds, walking to greener pastures each Spring, and returning home in the Fall. People walked the already established paths as the routes often took an easy contour at mid-elevation that passed above rolling hills and steep ridges at lower elevations. Elk, deer, goats, and sheep can easily walk on steep side slopes and under tree branches. Pedestrians, horse-riders, and human or burro-drawn carts can’t negotiate the low branches and angle of repose as naturally as Big Horn Sheep, so their trail alignments moved to slightly down-slope contours.

Staying along the contour beside the hard break in slope at around 8,000 to 8,600 feet in elevation gives a sweeping view of the valley and provides vegetation cover from exposure to harsh sunlight, stormy weather, and watchful eyes. Traveling on this gentle contour preferred by livestock animals also eliminates the multiple changes in elevation and extra mileage that comes with climbing up and over and down and back up again to cross the frequent valleys and finger ridges between the Rio Hondo and Red River watersheds. The steep grades dropping into and rising out of Valdez and Questa require long pulls of two miles to access the more level ground that allows for smoother passage. The trail crosses at low points in the canyons – on the Rio Hondo near Turley’s Mill and on the Red River near its confluence with Cabresto Creek.

A portion of the trail has been preserved by its continuous use by the Taos Pueblo Tribe. The Red Clay Trail travels from Taos Pueblo to their traditional mineral sources at Almagre, near the hydro-thermic scar between Questa and Cabresto Canyon. Residents along the Red Clay Way recall and anticipate the horse ride from Taos every August to gather pigments at Red Dirt Place. In the 1800s, travel on the trail and the annual trek to collect resources was a flashpoint between Native Americans and Rio Colorado villagers, at a time when conflicts were frequent and violent. Today, Taos Pueblo has a Cultural Easement that honors passage on the trail into perpetuity.

Archaeological evidence of the extensive use of the Kiowa Trail in Questa was found during the 1992 inventory for the Cabresto Bypass Road (aka Kiowa Road). Studies of the artifacts gave dates from at least 5,200 years ago to the late 1800s and suggest wide use of the trail for travel and trade by Archaic, Plains, Anasazi / Puebloan, Ute, and Apache cultures. Unfortunately, most traces of the old trail and the associated artifacts and campsites have been lost to road development, home construction on private land, and people collecting found artifacts.

More evidence of the Kiowa Trail is found in the high roads named “Kiowa Road” in Questa, Lama, and San Cristobal. The trail passes through the D.H. Lawrence Ranch in San Cristobal, which Lawrence first named “Kiowa Ranch.” When the University of New Mexico took over ownership of the Lawrence Ranch in 1956, they named a portion of the property “Kiowa Village,” which has appeared on USGS topographical maps ever since. The familiar names reflect the long-time use of the trail by the Oklahoma-based Kiowa Tribe into historic times.

The Kiowa Trail is at least 120 miles long, traveling from the high plains grasslands in eastern New Mexico and the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles, and westward through the Sangre de Cristo Pass near Fort Garland, Colorado. From that crossroads, it travels southward to the trading center at Taos Pueblo, and on to Taos Mountain Pass (aka Palo Flechado Pass) south of Ranchos de Taos. Both the northern and southern ends of the Kiowa Trail intersected with other major trails like the Camino Real, the Old Spanish Trail, and the Santa Fe Trail.

The general route of the Kiowa Trail begins at Taos and heads north to Valdez. The trail goes up Gallina Canyon through the D.H. Lawrence Ranch and Hawk Ranch, although alternate routes pass through Turley Mills subdivision and Lobo Ranch Road to old SR 3, or FR 493. The route skirts around San Cristobal and Garrapata Canyon and runs past the Lama Foundation and Lama. The trail is captured by Forest Road FR 970.55, where it finally descends into Questa at Largo Canyon as an old wagon road, since bladed by heavy machinery. The trail crossed the Red River near its confluence with Cabresto Creek on what is now South Kiowa Road, near where the first bridge into Questa may have been located.

Travelers on the Kiowa Trail would have stopped to rest, water-up, and camp at Rio Colorado, a beautiful, pastoral setting at the mouth of Red River Canyon. Located at almost 7,500 feet in elevation and situated at the entrance to the inner mountain region of the Sangre de Cristos, the Rio Colorado area is subject to sudden harsh weather and extreme changes in temperature. Stopping and camping on the trail, following herds of game, and shepherding flocks eventually led to people staying to live seasonally in the verdant valley.

One of the first villages along the trail was a 1050 to 1225 AD Pueblito, now buried beneath the Questa VFW cemetery named “El Pueblito.” Located about twenty miles from present-day Taos and Costilla, Questa is about a day’s horse ride or long walk on the trail. Way stops found about halfway from Questa in either direction are in San Cristobal and the northern Questa neighborhood of El Rito; both areas show archaeological evidence of the Kiowa Trail, camping sites, and small villages.

From Rio Colorado, the Kiowa trail headed north to the current neighborhood of El Rito where there was a possible Apache or Ute village on Latir Creek. The nomadic horse-riding bands may have lived in wiki-ups and lean-tos made of branches propped up by Juniper trees, and teepee-tent shelters covered with animal skins. Both the Apache and Ute people peeled and used the cambium layer from Ponderosa pine trees for medicine, food, and other needs; leaving big scars on the bark that also mark the general passage of the trail.

Little is known about the El Rito area or lifestyle of the early residents because no archaeological survey was conducted prior to the land grant parcel sales and new road and home construction. Like curious people everywhere, homeowners and hikers have picked up arrowheads and other artifacts and kept them a secret. While not illegal on private land, removing artifacts without reporting takes away the opportunity to learn and share about the lifeways of these cultures. Letting local archaeologists know about interesting artifacts and where they were found can help fill out the missing history.

North of El Rito between Costilla and San Luis, Colorado, and according to Spanish accounts from the 1700s, the trail passed by Ute lodges in villages with hundreds of residents. Comanche traveled the trail on horseback to raid in the Taos area until a peace treaty signed in 1786 kept them east of the Sangre de Cristos. Accounts from the US Army tell of battles on the trail with Apache and Ute bands in the 1840s and ’50s. The trail played an integral part during the Taos Rebellion against the US government in 1847, and also brought more traders, trappers, travelers, and settlers to the Questa area when New Mexico became a U.S. Territory in 1850.

Over time, the travel corridor that began as an animal-path-inspired walking route was realigned into a wagon road, a motor trail, and NM highways SR 3 and SR 522. The old alignments have been abandoned where they pass through private land, and in other segments are lost to county roads and Forest Service roads. Still, some portions of the old routes (where not crossed by private property) can be accessed on Public Lands by hikers, mountain bikers, horse-riders, motorcycles, ATV/UHVs, and in some places, automobiles. One of the most easily-accessed re-routes of the Kiowa trail is the Questa-Lama Road or Forest Road 493, also known as old SR3, running between San Cristobal and Questa. Another, more original route that became a wagon road is the high road between San Cristobal and Questa, now named Forest Road 970.55.